Friday, December 22, 2006

Happy Holiday, see you in 2007

Cheers,

David Rotor

Wednesday, December 20, 2006

Engaging internal clients

stolen from borrowing on skills and techniques from the sales world that allows the procurement team to engage with their clients in order to better understand their requirements and drive improved market share. For readers with experience in strategic sourcing, this level of engaging with a client is similar to what is done during a category sourcing exercise, but moves from being a event driven exercise to embedding it as a recurring procurement department business process. Here’s a graphic that provides a summary of the Client Engagement process.

Monday, December 18, 2006

Buying market share

Hi Tim,

I agree with your comment:

“No single metric defines supply management success. (Although, I personally believe that spend under management, as defined above, comes pretty darn close.)”

I’ve been using “spend under management” as the leading indicator (metric) for indirect procurement department effectiveness for several years now. I’ve found it effective across several industries, and even in the public sector. I also often refer to it as our department’s “market share” as executives in other business units understand the language, and often intuitively accept that market share growth is “good”.

I measure procurement market share against two axis. First, from a category manager’s perspective, what’s the corporate-wide compliance with each of our category offerings. For example, “the compliance rate for our preferred cell phone carrier was 89% last quarter”. The second axis is from a customer perspective; what’s our market share for a given client department. For example, “our market share of the COO’s spend is 92%”.

The value of this approach is it provides feedback to allow the procurement department to understand what the rest of the organization values, and what it does not. It also enables discussions around client requirements “why is our market share so low on the east coast?”

Cheers,

David Rotor

Thursday, December 14, 2006

Bending over backwards when you're buying

Standard supply and demand theory tries to explain how the amount of demand for a good or service and the amount of supply of that good or service interact. In relation to the amount of supply, the more demand there is for something, the higher the market price. The more supply there is in relation to the demand the lower the market price. Here's an illustration from the wikipedia entry.

This is the primary reason why buyers like to aggregate their demand - assuming adequacy of supply the more you buy (the red downward sloping line) the lower your per unit costs should be. Of course, in the real world sales teams don't pay much attention demand curves and will happily charge companies with larger volumes higher prices.

The backward bending demand curve is often used to describe labour markets "As a person's wage increases, they are willing to supply a greater number of hours working, but when the wage reaches an extremely high amount (say a wage of $4,000 per hour), the amount of labor supplied actually decreases". I can't recall ever seeing this behaviour in the market, or at least that couldn't more accurately be described as simply lowering supply and increasing price. It is worth having buyers understand, if only to help them understand that the standard curves don't always apply.

The u shaped cost curve, where the cost of a good or service initially decreases with volume and then begins to increase with additional volume is pretty common in real markets. There are many reasons, the main reason why companies accept a supplier having a u shaped cost curve is that the increased price they pay to a supplier that has a higher cost with more volume is often lower than the company would incur for introducing a new supplier "switching costs". The u shaped cost curve looks like this (don't blame wikipedia for this one).

I've run into this curve several times, usually while negotiating corporate-wide, or nation-wide deals for companies. Here are a few examples:

I've run into this curve several times, usually while negotiating corporate-wide, or nation-wide deals for companies. Here are a few examples:- Waste removal for a US based national housing REIT

- Travel agency and card services for a global telecommunication firm

- PCs for a national Canadian bank

- Office supplies for a national government

- Airline travel for a global media company

- Facility Management services for a commercial property REIT

- MRO and parts for a military

- Engineering supplies for a continental freight railway

- Food and snacks for a global media company

- Consulting services for a national government

- Packaging supplies for a global manufacturer

- Consumer shopping bags for a national retailer

- Recycling services for a brand-name retailer

With time, expertise, and the ability to test the market frequently, buyers can get a reasonable level of understanding of when a price curve for a good or service will begin to curve upwards. Often it is a function of both volume and geographic dispersion. It might cost a supplier more to service one city than another depending on how much business they have in each location. You might find that a supplier has production capacity constraints that you are bumping up against.

You want your buyers to lower the total cost of a category of good or service. They should consciously be aggregating and disaggregating volume to find the optimal "demand" offer to the market. That often means letting them pay a premium for a given geography or range of goods and services if that means an aggregate lower cost overall.

Cheers,

David Rotor

Tuesday, December 12, 2006

Shipping Costs - not quite a Marginal Revolution

Let's take a look at Levinson's comment. PricewaterhouseCoopers,(1) published "Cutting your distribution cost" in 2004. Here's a chart from the report, that shows that distribution costs remain substantially more than a footnote:

The data, which seems pretty representative from the companies I've looked at, shows that transportations costs ranged from 0.27% to 12.57% with a median of 2.15% expressed as a percentage of revenue. I can tell you that Macy's isn't at the low end of the range, and few companies would consider even 27 basis points of their revenue as a footnote.

In another client situation, a hospital organization in the US North East. They spent about $750M annually, with just under $4M of that going for freight and logistics. When we took a look at the $4M in spend, they had over 2,000 suppliers providing transportation services. Savings in this one category were on the order of $500K. While, perhaps, not the most important spend category for every firm, I'd take a hard look at them when you're trying to reduce your costs for goods and services.

Cheers,

David Rotor

(1) - Under "full disclosure", I previously worked for PricewaterhouseCoopers, as a Vice President of Global Sourcing.

Monday, December 11, 2006

Food bank economics

Good for them, a local non-profit community service organzation is using their market power to lower their operating costs, and improve the volume of goods they can deliver to their clientele. It left me wondering though; here's my line of thought.

First, as I understand it, food banks mostly serve "working poor", people with jobs or who are on some form of fixed income, who are not earning enough to meet their basic needs. Second, there is usually some form of rationing, such as one food hamper per family per week. Assuming for a moment these two assumptions are true, I wonder whether the food banks can extend their discounted prices to their clients? Their clients are presumably paying for some of their own food, at retail pricing, only getting a partial subsidy from their periodic free hampers. By extending the preferential pricing to their clients they would be able to further their organization's goals, and may in fact, also add to their market power, increasing their ability to negotiate preferential pricing for food.

Friday, December 8, 2006

Outsourcing business cases

I'm spending some time thinking through an outsourcing business case. The client has an expectation that the proposal will fit into their existing budget for the function (procurement and payables), independent legacy systems will be retired and new functionality will be added with the introduction of an integrated system, and ideally costs will be lowered. On the other side the service provider understandably wants to do all that, and turn a reasonable profit. So far, so good.

The difficulty is that the service provider's business case is turning up at about 150% of the existing budget. The work can be pretty quickly broken down into three areas to explore, plus one more:

The existing budget

This is a classic outsourcing issue, service provider's routinely strive to identify expand what's included in the existing budget, and client's routinely try to limit what's included. Direct costs are reasonably straight forward to nail down, allocated indirect costs such as contributions for space, corporate technology, support functions such as HR and accounting, are the usual areas that cause conflicts, and can determine whether a deal proceeds or fails.

The service provider's cost model

This tends to be a great area for "pursuit teams" (sales) to delve into in great depth. Most large outsourcing service providers have built wonderfully complex cost models to help them capture what it will cost to service an account. Routinely, I'll find that there is a bit of a fortress mentally around the cost model and it can often be as difficult to get the team to disclose line item details from the cost model as it is to get the client to share detailed budget information.

The first area to explore is whether the costs are market based or internally derived - don't accept the assertion from the cost team that they are market based, go and test the market yourself.

The second area to test is whether the internal costs have been inflated with an internal mark-up, again the cost team will routinely suggest they do not mark up costs, prove it for yourself.

The third area to examine are the overheads, are there too many people loaded onto the deal, are there costs loaded such as standard space or technology charges for people that have already had those costs modelled as direct costs for the contract, etc.

Going back over the last decade I've seen numerous cases where the cost team has contributed to proposals being, literally hundreds of millions of dollars over the market.

The service provider's pricing model

There is often little a pursuit team can do about the margin the company wants to earn from a contract, you win or lose in the market and margins will be adjusted to reflect that reality. What the pursuit team can do is vigorously target the "risk" model that can increase or decrease the margin calculation. Most (likely all) the major outsourcing service providers have developed formal risk management frameworks in their internal deal approval process. The one for the deal I'm looking at now runs about 200 questions, such as: Is the proposed deal a "factory" deal or a "fortress" deal? “Factory” means that it can be managed in a shared service facility, “fortress” means it is a unique offering that is customized for the client. Fortress deals have, in the model, a higher risk factor, and the discount rate applied to the price model is increased. Each of the 200 or so questions have similar impact on the discount rate. The pursuit teams need to spend time understanding the risk model, but often it is viewed as an administrative exercise, and the pursuit team doesn't ever really understand how the model will impact the success or failure of their proposal.

Strategic Sourcing

Outsourcing teams should also consider lowering the cost of goods and services in the function they are taking over by using strategic sourcing. I won't get into it in this post, but it's often possible to lower those costs by 10% or more, enough that many deals will live or die on the application of sourcing to the deal. Spending time to have an expenditure analysis performed to determine if there is an opportunity is well worth considering.

Cheers,

David Rotor

Thursday, December 7, 2006

Phil Nimmons speaks

Throughout the piece I could hear Phil's desire to have the piece represent the musicans and their instruments talk to each other. I found it was like a really successful party where there are a bunch of interesting people chatting to each other with sometimes one and sometimes several conversation threads happening at once. One of the highlight soloist bits was Alex Dean on sax doing a bit of "free-blowing". I don't know if it was intentional but it sure seemed to be a homage to the way Phil is best known for playing, just this side of out of control, arms, legs, and body practically bouncing off the stage. Elaine and I and a few friends thoroughly enjoyed seeing the band live again, getting 20 people on stage playing live jazz doesn't happen very often in Canada.

Tuesday, December 5, 2006

Auditory consumption

Monday, December 4, 2006

Dell in the news

Standard practice, in many industries not just PC assemblers, is to develop highly analytical models using meantime to failure and other factors to determine how many of which parts are going to be needed to support the repair and warranty requirements for a product. The manfacturer will then run a production run to stock inventory to support this expected consumption. The Dell model changed the PC industry, what Dell realized was that the fleet of PCs they sold were themselves a supply chain of inventory for the repair and warranty business. They developed better models than their competitors, largely based on cannibalizing returned and broken PCs for good parts. The cost advantage from this model began at over 10% and slowly declined over several years.

Friday, December 1, 2006

Buying a cell phone this season? You may want to wait until March.

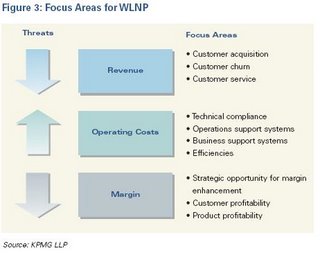

As a consumer you won't have much opportunity to personally influence these factors, but you should see the market impact of WLNP very quickly come March. I would recommend holding off on signing up for a new multi-year wireless contract until the impact is reflected in the market. Corporate buyers should think about not only waiting for the market impact of WLNP, but also what they can do to influence the focus areas that KPMG identifies for each factor. A couple of obvious areas are to lower the cost to service your account, such as moving to web-based reporting and eliminating mailed statements. Can you allow the carrier to sell premium services or hardware directly to your employees? As always, understanding the seller's issues "market knowledge" is key to negotiating the best deal for your company.